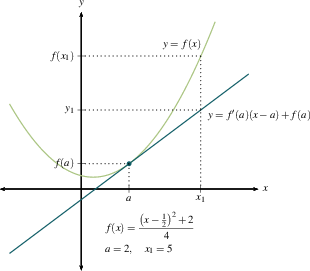

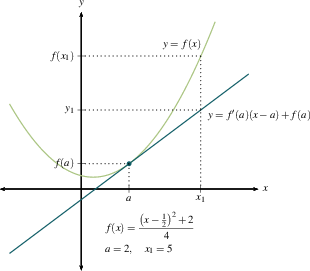

Derivatives can be used to get very good linear approximations to functions. By definition, $$f'(a) = \lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}.$$ In particular, whenever $x$ is close to $a$, $\frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}$ is close to $f'(a)$, i.e., $\frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}\approx f'(a)$. Thus $f(x) - f(a)\approx f'(a) (x-a)$, so $$f(x) \approx f(a) + f'(a) (x-a)$$ whenever $x$ is close to $a$.

The function $L(x) = f(a) + f'(a) (x-a)$ is called the linearization of $f(x)$. The line $y=L(x)$ goes through $\big(a, f(a)\big)$ with slope $f'(a)$, so it is the line tangent to $y=f(x)$ at $\big(a, f(a)\big)$. You can see this by finding the line tangent to $f$ at $x=a$:

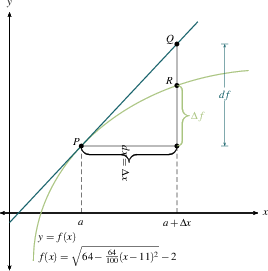

Differentials are another name for the same idea.

Let $\Delta x = x-a$ be the change in $x$, and $\Delta f = f(x) -

f(a)$ be the change in $f$. And let $dx=x-a$, and let $df= f'(a)

dx$.

Our approximation is then $$\Delta f \approx df.$$

The actual changes $\Delta f$ and $\Delta x$ are the rise and run

along the secant line between $P=\big(a, f(a)\big)$ and $R=\big(x,

f(x)\big)$.

The differentials $df$ and

$dx$ are the rise and run along the tangent

line as we go from $a$ to $x$.