Throughout, we assume $f$ and $g$ are arbitrary functions and $a,b,c,m$ and $M$ are constants:

|

Items 2 and 3 are direct results of the definition of the

definite integral as a limit, since the limit of a sum (or

difference) of functions is the sum (or difference) of the limits,

and since you can pull a constant out of a limit. Item 4 is

easy to see if you think of the limit definition of the integral

-- $\Delta x$ becomes $\frac{a-b}{n}$ instead of $\frac{b-a}{n}$

and thus is negated.

DO: Sketch appropriate

graphs and convince yourself that items 1 and 5 above make

sense.

DO: Sketch a graph of some $f$ with $a<b<c$ and convince yourself that item 6 above makes sense. Note: $b$ does not have to be between $a$ and $c$ for item 6 to be true. This is harder to see, but play with it if you wish.

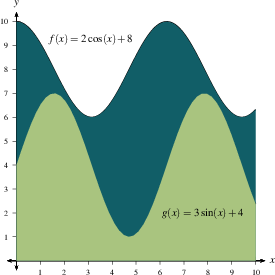

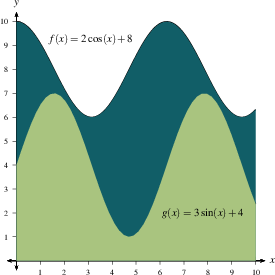

DO: Sketch appropriate

graphs and convince yourself that the three properties below

make sense.

|

In other words, we can compare $f$ to $0$, we can compare $f$ to $g$, and we can compare $f$ to $m$ and $M$.

These properties are easy to visualize if you think about area and graphs, as you did above. If $f(x) \ge g(x)$, then the curve $y=f(x)$ lies above the curve $y=g(x)$, so there is more area under the $f$ curve than under the $g$ curve.

But these properties apply even when we are dealing with negative functions or applications that have nothing to do with area. To see why the second property holds without thinking of areas and graphs, notice that if $f(x) \ge g(x)$ for all $x \in [a,b]$, then $$ f(x_i^*) \ge g(x_i^*) \quad \text{and so} \quad f(x_i^*)\,\Delta x \ge g(x_i^*)\,\Delta x, \text{ for each } i=1,\ldots,n. \text{ Hence, }$$ $$ {\sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)\, \Delta x} \ge {\sum_{i=1}^n g(x_i^*)\, \Delta x}. \text{ Then by limit laws, } {\lim_{n \to \infty}\, \sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)\, \Delta x} \ge {\lim_{n \to \infty}\,\sum_{i=1}^n g(x_i^*)\, \Delta x}, $$ and thus by the definition of integral $$\int_a^b f(x)\, dx \ge \int_a^b g(x)\, dx. $$