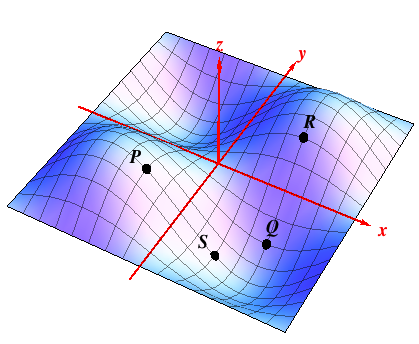

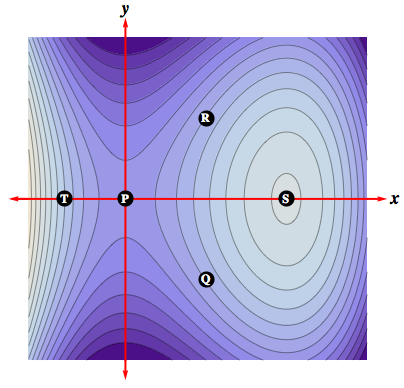

Solution: at $Q$, for instance, the surface slopes up for fixed $x$ as $y$ increases, so $f_y\bigl|_{Q} > 0$, while the surface remains at a constant level at $Q$ in the $x$ direction for fixed $y$, so $f_x\bigl|_{Q}= 0$. On the other hand, $$f_x\bigl|_{R} \,=\,0,\quad f_y\bigl|_{R} \,>\, 0\,, \qquad f_x\bigl|_{P} \,<\, 0,\, \quad f_y\bigl|_{P} \,=\, 0 \,.$$ But what happens at $S$?