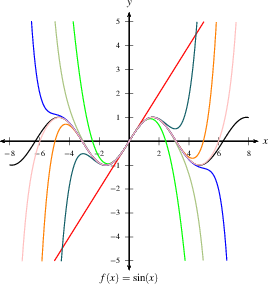

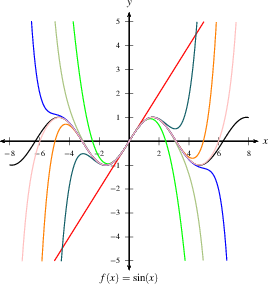

This is another graph of the same function, $f(x)=\sin(x)$, in black. This graph includes (unlabled) the Taylor polynomials that are in the graph above, with the addition of $T_9(x),T_{11}(x)$, and $T_{13}(x)$.

Probably the most important application of Taylor series is to use their partial sums to approximate

functions. These partial sums are (finite)

polynomials and are easy to compute. We call them Taylor polynomials.

| An $n^{th}$

degree Taylor polynomial is the polynomial of degree

$n$, consisting of the partial sum of the Taylor series up

to the $n^{th}$ power, denoted $T_n(x)$: $\begin{eqnarray} T_n(x)&=&f(a)+f'(a)(x-a)+\frac{f''(a)}{2!}(x-a)^2+\frac{f^{(3)}(a)}{3!}(x-a)^3+\cdots+\frac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x-a)^n\\ &=&\sum_{k=0}^n\frac{f^{(k)}(a)}{k!}(x-a)^k \end{eqnarray}$ |

You may recognize the first Taylor polynomial above. (Does it look familiar? Take a moment to think about this.) It is the linearization $L(x)$ of $f(x)$, which is just the equation of the tangent line of $f$ at $x=a$ that we used previously to approximate values of $f$ near $x=a$: $\quad f(x) \approx L(x) = f(a) + f'(a) (x-a)=T_1(x).$

Taylor polynomials extend the idea of linearization. To approximate $f$ at a given value of $x$, we will use $T_n(x)$ for a value of $n$ that gives a good enough approximation. We see from $T_n(x)$ above that we will need to find an $x$-value $a$ at which we can evaluate the derivatives of $f$. Our approximations get better the more terms we include, and they also allow us to get further from $a$ and still have a good approximation.Example: Find the Taylor polynomial of degree $7$

for $f(x)=\sin x$ centered at $x=0$.

Solution: We will compute this as if we didn't

already know the Taylor series for sine. We look at $T_n(x)$

above, and see we need to find evaluate $f(x)=\sin(x)$ and its

derivatives at $a=0$.

$\begin{array}{lll}

f(0)&=\sin(0)&=0\\

f'(0)&=\cos(0)&=1 \quad\text{ and then this pattern

repeats, so that }\\

f''(0)&=-\sin(0)&=0\\

f^{(3)}(0)&=-\cos(0)&=-1\\

\end{array}$ $\begin{array}{ll}

f^{(4)}(0)&=0\\

f^{(5)}(0)&=1\\

f^{(4)}(0)&=0\\

f^{(5)}(0)&=-1\\

\end{array}$

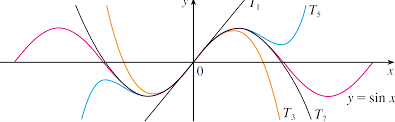

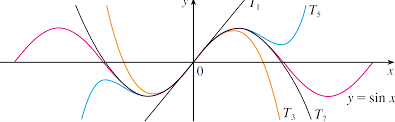

| This graphic shows $f(x)=\sin(x)$ in red,

then the linear approximations $T_1(x)$, $T_3(x)$, $T_5(x)$

and $T_7(x)$. You can see that as $n$ gets larger,

$T_n(x)$ matches the sine curve better, and matches it

farther from 0. cims.nyu.edu

|

|

This is another graph of the same function, $f(x)=\sin(x)$, in black. This graph includes (unlabled) the Taylor polynomials that are in the graph above, with the addition of $T_9(x),T_{11}(x)$, and $T_{13}(x)$. |

|