Theorems for and Examples of Computing Limits of Sequences

Evaluating limits of sequences using limits of functions

The limit of a function is the limit of continuous values of the

function, while the limit of a sequence is a limit of discrete

numbers. Nonetheless, we recognize that if a continuous

function passes through all numbers of a sequence, then the

convergence or divergence of the sequence matches the convergence

or divergence of the function. To see this, just picture the

graph of a sequence (earlier in this module) and draw the curve

through the dots, letting the curve be $f(x)$, and hence

$f(n)=a_n$ for the positive integers $n$.

Theorem

1: Let $f$ be a function with $f(n)=a_n$ for

all integers $n>0$.

If $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty}f(x)=L$, then

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}a_n=L$ also.

|

This theorem allows use to compute

familiar limits of functions to get the limits of sequences.

Example 1: By the theorem, since

$\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{1}{x^r}=0$ when $r>0$,

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{1}{n^r}=0$ when

$r>0$. Learn this example.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Example 2: Evaluate

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{2n}{3n-4}$.

Solution 2: By dividing the top and the bottom by

$n$, we get $\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{2}{3-\tfrac 4

n}$. By the previous example, $\tfrac 4 n$ converges to 0,

so we get

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{2n}{3n-4}=\frac{2}{3}$.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Example 3: Evaluate

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{5n}{e^n}$. DO: To solve this limit, first

compute $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{5x}{e^x}$ before

reading on.

Solution 3: We use l'Hospital's Rule.

$\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{5x}{e^x}\underset{\fbox{$\tfrac

\infty \infty\,,\,

\text{l'H}$}}{=}\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{5}{e^x}=0$. Thus

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{5n}{e^n}=0$ by Theorem 1.

Notice that we cannot take a derivative of a sequence, since a derivative exists only if the function is

continuous, and sequences are not continuous.

Yet, because of our theorem, we can use l'Hopital's rule on the

associated (continuous) $f(x)$ and compute our limit by taking

derivatives. We get the limit of

the sequence by evaluating the limit of the function.

Alternating sign sequences

Unlike continuous functions, sequences sometimes have alternating

positive and negative values, such as $a_n=\frac{(-1)^n}{n}$.

We cannot find a nice function $f$ with

$f(x)=\frac{(-1)^x}{x}$. (Why not?)

Fortunately, we have another theorem to help us with these

sequences.

Theorem 2: $\displaystyle

\lim_{n\to\infty}a_n=0$ if and only if

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}|a_n|=0$.

Warning: This is

only true when the limits are equal to 0.

|

This theorem allows us to evaluate the limit of a sequence with both

positive and negative values by evaluating the limit of its absolute

value (using Theorem 1, for example). If this limit is 0, our

original limit is zero.

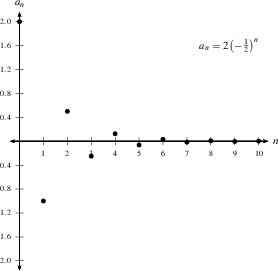

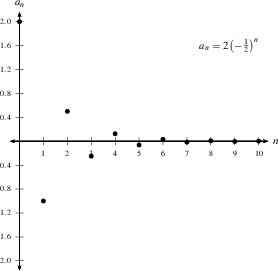

To see why this theorem makes sense, think about this graph

of a sequence $a_n=2\frac{(-1)^n}{2}$, which converges to

0. The graph of $\left\{|a_n|\right\}$ would flip all

the negative points to their positive values, giving a

sequence steadily decreasing to zero. |

|

Example 4: By Theorem 1, since

$\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty}r^x=0$ when $0<r<1$ (remember exponential functions?),

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}r^n=0$ when $0<r<1$.

By Theorem 2, this extends to $-1<r<1$. If $r>1$

or $r\le-1$, the limit diverges. (DO:

what happens when $r=1$?) Summarizing:

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}r^n

\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\text{converges }&\text{ if

}-1<r\le

1\\\text{diverges}&\text{otherwise}\end{array}\right.$

Learn this. We will use it

frequently.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Example 5: Let $

a_n=(-1)^n\frac{3^{n+2}}{5^n}$. We will take the the

absolute value of our sequence, which here simply means ignoring

the alternating sign $(-1)^n$, and take a limit to see if we get

0. Rewrite to get

$|a_n|=3^2\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)^n=9\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)^n$.

We evaluate

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}|a_n|=

\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{3^{n+2}}{5^n}=9\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)^n=9\cdot

0=0$, by Example 4 with $r=\tfrac 3 5$, since

$-1<r<1$. Therefore,

$\displaystyle\lim_{n\to\infty}a_n=\lim_{n\to\infty}(-1)^n\frac{3^{n+2}}{5^n}=0$

by Theorem 2.