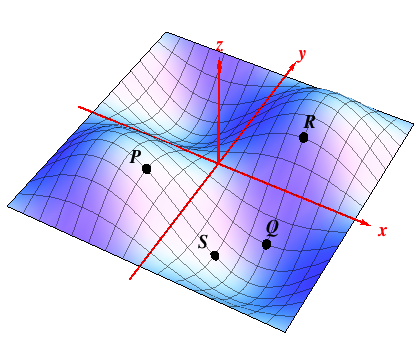

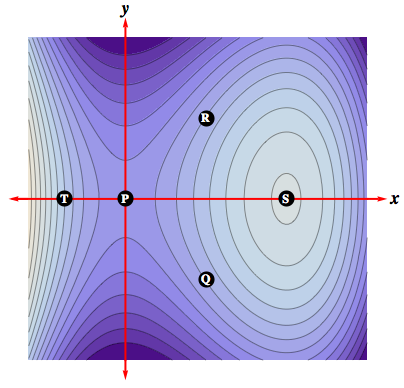

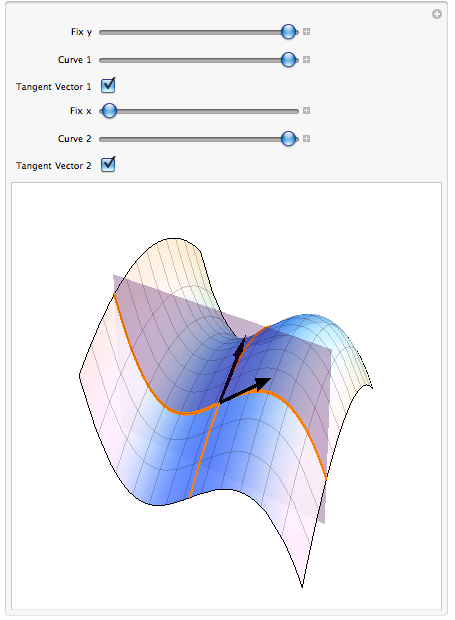

Start with the surface $$z \ = \ f(x,\, y) \ = \ 3x^2 -y^2 -x^3 +2,$$ shown to the right. Then $$f_x \ = \ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \ = \ \frac{\partial } {\partial x}\, \bigl( 3x^2 -y^2 -x^3 +2\bigl) \ = \ 6x -3x^2 \,.$$ To understand what this means, fix a value of $y$, say $y=-1$. Equivalently, slice the surface $z=f(x,y)$ with the plane $y=-1$, as in the figure. The cubic curve of intersection is shown in orange and can be given the parametrization $${\bf r}(x)\, = \, \bigl\langle\, x,\, -1,\, f(x,\,-1)\,\bigl\rangle\,=\, \bigl\langle\, x,\, -1,\, 3x^2 -x^3 +1\,\bigl\rangle\,.$$ A vector tangent to this orange curve is $${\bf r}'(x)\ = \ \bigl\langle\, 1,\, 0,\, 6x -3x^2\,\bigl\rangle \ = \ \bigl\langle\, 1,\, 0,\, f_x\,\bigl\rangle\,,$$ Thus $f_x$ gives the slope of the surface $z = f(x,\,y)$ as we move in the $x$-direction.

Likewise, if we fix $x= 1$, we see that $f_y$ gives the slope of the other orange curve (obtained by intersecting our surface with the plane $x=1$) as we move in the $y$-direction. Thus

The value $\displaystyle\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\Bigl|_{(a,\,b)}$ is the Slope in the $x$-direction,

The value $\displaystyle\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\Bigl|_{(a,\,b)}$ is the Slope in the $x$-direction,