Example 1: Evaluate the iterated integral $$I \ = \ \int_0^6 \left(\int_{x/3}^2\, x\,\sqrt{1+y^3}\, dy\right)dx\,.$$

Solution: The inner integral is hopeless, and nothing you have learned so far in calculus will help. Instead, we need to swap the order of integration.

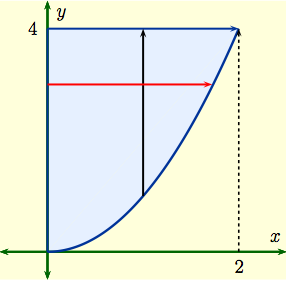

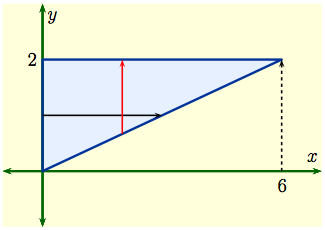

The region of integration is the blue triangle shown on the left, bounded below by the line $y=\frac{x}{3}$ and above by $y=2$, since we are integrating $y$ along the red line from $y=\frac{x}{3}$ to $y=2$. Since we are integrating $x$ from 0 to 6, the left edge of the triangle is at $x=0$, and we integrate all the way to the corner at $(x,y)=(6,2)$.

Treating this as a Type II region, we fix $y$ and integrate with respect to $x$ along the black line. Then $$I \ = \ \int_0^2 \left(\int_{0}^{3y}\, x\,\sqrt{1+y^3}\, dx\right)dy\,.$$ Now the inner integral is easy, and gives $$\int_{0}^{3y}\, x\, \sqrt{1+y^3} dx\ = \ \Bigl[\,\frac{1}{2}x^2\sqrt{1+y^3}\, \Bigr]_0^{3y} \ = \ \frac{9}{2}y^2 \sqrt{1+y^3}\,,$$ with the ugly factor of $\sqrt{1+y^3}$ just coming along for the ride. We then have $$I =\int_0^2 \frac92 y^2 \, \sqrt{1+y^3}\,dy = \int_1^9 \frac32 \sqrt{u}\; du = 26\,,$$ using the substitution $u = 1+y^3$.