M 408C Approximating the Change in Rocket Altitude with Riemann Sums S*(P) Spring 2002

Recall the Rocket Altitude function used in Example 1 of Part IV of the Trapezoid Problem Handout:

Example 1: Suppose that the function y = f(t) = 5t2 , 0 < or = t < or = 10, calculates the altitude (# of feet above

the ground) of a particular rocket at any time t seconds during the first 10 seconds after its liftoff.

It is shown there that the formula for the Instantaneous Velocity (equal to the Instantaneous Rate of Change of the Altitude) at any time t is Velocity = 10 t ft/sec, which is the same as the formula for the derivative f '(t) = 10t ft/sec .

The process of evaluating the derivative

f '(t) =![]() allows

us to analyze the function which calculates the position of the rocket (here,

the altitude) and, through differentiation, determine the rate at which that

position is changing (i.e., the velocity) at a particular time.

allows

us to analyze the function which calculates the position of the rocket (here,

the altitude) and, through differentiation, determine the rate at which that

position is changing (i.e., the velocity) at a particular time.

The process of evaluating an integral allows us to reverse this analysis in some sense; integration allows us to analyze the function which calculates the velocity (i.e., the rate at which the position is changing) and, by calculating the DEFINITE INTEGRAL over an interval of time [a,b] , determine the amount of increase in rocket altitude (i.e., the actual change in position of the rocket) during the interval of time [a,b] .

To motivate the definition of the Integration Process and

the definition of the new concepts and new notations (Partition P of interval

[a,b] into n sub-intervals, the ith sub-interval ![]() , width

, width ![]() of the ith

sub-interval, etc.), let us consider how the determination of the change in

altitude of the rocket from an analysis of the velocity function, y =

velocity = f(x), might be accomplished.

of the ith

sub-interval, etc.), let us consider how the determination of the change in

altitude of the rocket from an analysis of the velocity function, y =

velocity = f(x), might be accomplished.

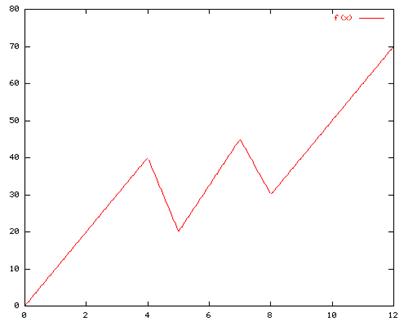

Suppose that the engineers designing this rocket altered the fuel formula and engine operation so that now its height function and velocity function have changed. Now the engineers are able to determine that the function, y = f(x) as defined below, calculates the velocity (ft/sec) of the rocket at any time x seconds during the first 12 seconds after lift-off. Note that this particular velocity function f(x) is not in any way an improvement over the one before, but it is designed to be useful for illustrating the integration process. Also, the variable used for time is x now and not t .

Here is the new velocity function y = f(x) ft/sec velocity at any time x , 0 < or = x < or = 12 :

f(x) =

This function does look intimidating, but in fact it will be easy to work with once a few special points on the graph are identified. Below, the graph is shown again with these special points identified.

A first, very gross, estimate of the increase in

altitude during the first 12 seconds of ascent can be found by answering the

following question:

A first, very gross, estimate of the increase in

altitude during the first 12 seconds of ascent can be found by answering the

following question:

Question: If the rocket velocity had been constant during the whole 12-second interval [0,12] and if that assumed constant velocity were equal to the actual velocity of the rocket at the end of the interval [0,12], then by how much would the altitude have increased during the whole interval [0,12] ?

The velocity at time x = 12 sec is y = f(12) = 70 feet/sec . If the rocket traveled at the rate of 70 ft/sec during the complete 12-second interval, then the increase in altitude equals the distance traveled which equals (rate) (time) = (70 ft/sec) (12 sec) = 840 feet.

Question: Is this an under-estimation or an over-estimation of the increase in altitude during the interval [0,12] ? (Answer: ----------Don't look yet, think about it ---------------------------- Over-estimation. )

We are going to systematically improve on this approximation by dividing the interval [a,b] = [0,12] into a collection of sub-intervals, that is by forming partitions of the interval [a,b] = [0,12] , and then we will ask what the increase in altitude would have been if the velocity had been constant during each of the sub-intervals of time in the partition of the whole interval of time [a,b] = [0,12].

Notation:

A Partition P of an interval [a,b] is a decomposition of [a,b] into a collection of sub-intervals which meet only at endpoints and which join together to fill out the whole interval [a,b] . For example, one partition P of the interval [0,12] is the collection of 5 sub-intervals: [0, 4], [4, 5], [5, 8], [8, 11], [11, 12] . A Partition P is specified by listing the endpoints of the sub-intervals in the partition. Thus, this 5-sub-interval partition is specified by saying, "Partition P is the partition P = { 0, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12 }". (A listing of 6 numbers!)

The generic partition P of the generic interval [a,b] is specified as: "P = {![]() }

, where

}

, where ![]() and

and

![]() and

n is the number of sub-intervals in partition P."

and

n is the number of sub-intervals in partition P."

When the interval [a,b] is divided into sub-intervals, the symbol "n" will always represent the number of sub-intervals that the whole interval [a,b] is divided (partitioned) into.

REFINEMENT #1:

We will first partition the 12-second time interval [0,12] into n = 2 sub-intervals, both of which will conveniently have a width of 6 seconds. The two sub-intervals are: [0,6] and [6,12] .

Question: What is the maximum velocity M1 of the rocket during the first sub-interval, sub-interval1 = [0,6] ?

Answer: Maximum f(x) velocity value on ![]() = [0,6] is M1

= 40 ft/sec . (Refer to graph above)

= [0,6] is M1

= 40 ft/sec . (Refer to graph above)

Question: What is the maximum velocity M2 of the rocket during the 2nd sub-interval, sub-interval2 = [6,12] ?

Answer: Maximum f(x) velocity value on ![]() = [6,12] is M2

= 70 ft/sec . (Refer to graph above)

= [6,12] is M2

= 70 ft/sec . (Refer to graph above)

We are considering here the partition P1 of [0,12] , where P1

= { ![]() } = { 0 , 6, 12 } which

divides the interval [0,12] into n = 2 sub-intervals:

} = { 0 , 6, 12 } which

divides the interval [0,12] into n = 2 sub-intervals: ![]() = [0,6]

and

= [0,6]

and ![]() =

[6,12] . Note:

=

[6,12] . Note: ![]() always represents the last

sub-interval in the partition of [a,b] under discussion.

always represents the last

sub-interval in the partition of [a,b] under discussion.

Question: If the rocket velocity had been constant during each of the

two sub-intervals ![]() , ( i = 1, 2 ) , and

if that assumed constant velocity were equal to the maximum actual velocity of

the rocket Mi during each sub-intervali, ( i = 1, 2

) , then by how much would the altitude have increased during the whole

interval [0,12] ?

, ( i = 1, 2 ) , and

if that assumed constant velocity were equal to the maximum actual velocity of

the rocket Mi during each sub-intervali, ( i = 1, 2

) , then by how much would the altitude have increased during the whole

interval [0,12] ?

Answer: M1 = 40 ft/sec is the maximum f(x) velocity

on ![]() =

[0,6] = sub-interval1.

=

[0,6] = sub-interval1.

M2 = 70 ft/sec is the maximum f(x) velocity

on ![]() =

[6,12] = sub-interval2 =

=

[6,12] = sub-interval2 = ![]() .

.

The widths of the sub-intervals (here, lengths of time) are ![]() = 6 sec

and

= 6 sec

and ![]() =

6 sec.

=

6 sec.

Thus, with this assumption of constant velocity during each of the sub-intervals, where the constant velocity is the maximum velocity during each sub-interval, the increase in altitude would have been:

M1 ![]() + M2

+ M2 ![]() = ( 40

ft/sec ) ( 6 sec ) + ( 70 ft/sec ) ( 6 sec ) = 240 + 420 feet =

660 feet .

= ( 40

ft/sec ) ( 6 sec ) + ( 70 ft/sec ) ( 6 sec ) = 240 + 420 feet =

660 feet .

It is more traditional to write the width of the ith

sub-interval as ![]() rather that

rather that ![]() , and from

this point on

, and from

this point on ![]() will be used to represent the

width of the ith sub-interval .

will be used to represent the

width of the ith sub-interval .

Question: Is this an under-estimation or an over-estimation of the increase in altitude during the interval [0,12] ? (Answer: ----------Don 't look yet, think about it.)

It is an over-estimation because the assumed constant velocity was the maximum of all the velocities attained during each sub-interval, so the actual increase in altitude during each sub-interval was less than the increase in altitude resulting from the assumed constant velocity.

REFINEMENT #2:

We form the partition P2 =

{ ![]() }

= { 0 , 3, 6, 9, 12 } which partitions the interval [0,12] into n = 4

sub-intervals. See the graph to the below:

}

= { 0 , 3, 6, 9, 12 } which partitions the interval [0,12] into n = 4

sub-intervals. See the graph to the below:

|

Question: For each i, i = 1, 2, 3, 4, what is the maximum f(x) velocity Mi during sub-intervali ? That is, what are Mi, ( i = 1, 2, 3, 4 ) ? Said another way, what are M1, M2, M3, and M4 ?

M1 is the maximum f(x) velocity during sub-interval1 = [0,3] : M1 = 30 ft/sec . Similarly, M2 = 40 ft/sec; M3 = 45 ft/sec; M4 = 70 ft/sec .

Question: What are the widths ![]() , ( i = 1, 2, 3, 4 )

, of the n=4 sub-intervals ?

, ( i = 1, 2, 3, 4 )

, of the n=4 sub-intervals ?

![]() =

= ![]() = 3 – 0 = 3

sec ,

= 3 – 0 = 3

sec , ![]() =

= ![]() = 6 – 3 = 3

sec .

= 6 – 3 = 3

sec .

![]() =

= ![]() = 9 – 6 = 3

sec ,

= 9 – 6 = 3

sec , ![]() =

= ![]() = 12 – 9 = 3

sec .

= 12 – 9 = 3

sec .

(Note: The fact that these widths are all the same is a result of our

choice at the start to divide the original interval [a,b] = [0,12] into 4

sub-intervals, all of uniform width. This "uniform

width" choice is NOT

REQUIRED and so the ![]() 's are not always

constant

widths as they are here!)

's are not always

constant

widths as they are here!)

Question: What would the increase in altitude have been if the rocket velocity over each sub-interval had been constant and that constant velocity had been the maximum Mi over each sub-interval ?

Answer: M1 ![]() + M2

+ M2 ![]() + M3

+ M3

![]() +

M4

+

M4 ![]() =

= ![]() = (30) (3) + (40)

(3) + (45) (3) + (70) (3) = 90 + 120 + 135 + 210 = 555 feet .

(This is also an over-estimation.)

= (30) (3) + (40)

(3) + (45) (3) + (70) (3) = 90 + 120 + 135 + 210 = 555 feet .

(This is also an over-estimation.)

Definition: Given function f , given interval [a,b] , and

given partition P = { ![]() } with n

sub-intervals of width

} with n

sub-intervals of width ![]() ,

, ![]() , . . . ,

, . . . , ![]() , and if, for each

i, ( i = 1, 2, . . ., n ), Mi = the Maximum

f(x) value on

the ith sub-interval, then the P Upper Sum for f ,

Uf (P) , is the summation number:

, and if, for each

i, ( i = 1, 2, . . ., n ), Mi = the Maximum

f(x) value on

the ith sub-interval, then the P Upper Sum for f ,

Uf (P) , is the summation number:

Uf (P)

= ![]() .

.

Using this terminology, with the rocket velocity function y = f(x) for

the function f in the definition, and with interval [a,b] = [0,12],

and with partition P = { 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 } as directly above, then the

increase-in-altitude estimate, M1 ![]() + M2

+ M2 ![]() + M3

+ M3

![]() +

M4

+

M4 ![]() = 555 feet, shows that the

P Upper Sum for f is:

= 555 feet, shows that the

P Upper Sum for f is:

Uf (P)

= ![]() =

555 , where n = 4 .

=

555 , where n = 4 .

UNDER-ESTIMATE # 1

Next, we will use the same partition P2 = { 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 } as before, and we will assume again that the rocket velocity was constant during each of the sub-intervals, but this time we will assume that the constant velocity during each sub-interval is mi = the minimum f(x) velocity of all the actual velocities of the rocket attained during the sub-interval. Thus, looking at the graph above, we see that:

m1 = 0 ft/sec , m2 = 20 ft/sec , m3

= 30 ft/sec , and m4 = 40 ft/sec. We still have ![]() = 3, (

i = 1, 2, 3, 4 ) .

= 3, (

i = 1, 2, 3, 4 ) .

With these "minimum f(x) velocity" assumptions, the increase in altitude would have been:

m1 ![]() + m2

+ m2 ![]() + m3

+ m3

![]() +

m4

+

m4 ![]() =

= ![]() = (0) (3) + (20)

(3) + (30) (3) + (40) (3) = 0 + 60 + 90 + 120 = 270 feet .

(This is an under-estimation because minimum f(x) velocities were used

for the constant velocities.)

= (0) (3) + (20)

(3) + (30) (3) + (40) (3) = 0 + 60 + 90 + 120 = 270 feet .

(This is an under-estimation because minimum f(x) velocities were used

for the constant velocities.)

Definition: Given function f , given interval [a,b] ,

and given partition P = { ![]() } with n

sub-intervals of width

} with n

sub-intervals of width ![]() ,

, ![]() , . . . ,

, . . . , ![]() , and if, for each

i, ( i = 1, 2, ... , n ), mi = the minimum

f(x) value on

the ith sub-interval, then the P Lower Sum for f ,

Lf (P) , is the summation number:

, and if, for each

i, ( i = 1, 2, ... , n ), mi = the minimum

f(x) value on

the ith sub-interval, then the P Lower Sum for f ,

Lf (P) , is the summation number:

Lf (P)

= ![]() .

.

Using this terminology, with the rocket velocity function y = f(x) for

the function f in the definition, and with interval [a,b] = [0,12],

and with partition P = { 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 } as directly above, then the

increase-in-altitude estimate, m1 ![]() + m2

+ m2 ![]() + m3

+ m3

![]() +

m4

+

m4 ![]() = 270 feet, shows that the

P Lower Sum for f is:

= 270 feet, shows that the

P Lower Sum for f is:

Lf (P)

= ![]() =

270 , where n = 4 .

=

270 , where n = 4 .

Note: It will always be the case that, no matter what particular partition P of [a,b] is used, the

P Lower Sum for f = Lf (P) < or = Uf (P) = P Upper Sum for f . ( Why? )

Consider partition P3 of [a,b] = [0,12] where P3 = { 0, 1, 3, 5, 6, 7.2, 9, 12 } (here, n = 7) . The sub-intervals for P3 are: [0,1] , [1,3] , [3,5] , [5,6] , [6, 7.2] , [7.2, 9] , [9,12] . Note how the sub-intervals in P3 can be collected together into groupings which themselves are partitionings of the sub-intervals in the partition P2.

For example, [0,1] and [1,3] in P3 together make a partition of the sub-interval [1,3] in P2. Also, [6, 7.2] and [7.2, 9] in P3 together make a partition of the sub-interval [6,9] in P2. When this occurs, that is, when the sub-intervals of one partition P' of [a,b] form partitionings of the sub-intervals of another partition P of [a,b], we say that the partition P' is a Refinement of the other partition P of [a,b].

Comparing the Upper and Lower sums of f for these two partitions, P and its refinement P', we find that as the refinement of partitions get finer and finer, the P' Lower Sums of f get larger and larger and the P' Upper Sums decrease, but still all the Uppers sums are greater that or equal to all the Lower sums. Thus, when P' is a refinement of P, Lf (P) < or = Lf (P') < or = Uf (P') < or = Uf (P) .

Looking back at partition P3 = { 0, 1, 3, 5, 6, 7.2, 9, 12

} with interval widths, ![]() = 1 ,

= 1 , ![]() = 2 ,

= 2 , ![]() = 2 ,

= 2 , ![]() = 1 ,

= 1 , ![]() = 1.2 ,

= 1.2 , ![]() = 1.8 ,

= 1.8 , ![]() = 3 , we

can illustrate the concept of the Norm of a partition P, written || P

|| ; the Norm of Partition P is the maximum width of all the widths of

the sub-intervals of P. For P3, the Norm of P3 is || P3

|| = 3 =

= 3 , we

can illustrate the concept of the Norm of a partition P, written || P

|| ; the Norm of Partition P is the maximum width of all the widths of

the sub-intervals of P. For P3, the Norm of P3 is || P3

|| = 3 = ![]() , here.

, here.

Definition of the Definite Integral I of function f from a

to b: I = ![]() .

.

We can form hundreds of partitions P of interval [a,b] , some having hundreds, thousands, or even hundreds-of-thousands of sub-intervals. As the number n , the number of sub-intervals, increases and as the Norm of the partitions approach arbitrarily close to 0, the Lower sums Lf (P) increase and the Upper sums Uf (P) decrease and they become closer and closer together, but Lf (P) never becomes greater than Uf (P) . There is, in fact, only one number, I, which can fit in-between all the upper and lower sums of f for every partition P of [a,b].

That is, there is one unique number, I , called "The Definite Integral of function f from a to b" , which is such that, for every partition P of [a,b] that exists, the number I is "in-between" the P Lower sum of f and the P Upper sum of f ; and so Lf (P) < or = I < or = Uf (P) for every partition P of [a,b] . Thus,

Lf (P) < or = ![]() < or =

Uf

(P) for every partition P of [a,b], and no other number

does this.

< or =

Uf

(P) for every partition P of [a,b], and no other number

does this.

Integration is the process of determining this definite integral number

I, and it will be the key step in determining the exact increase in the

altitude of the rocket, call it ![]() , during the first 12 seconds

after lift-off. In fact, we can use logical reasoning to conclude that this number

I =

, during the first 12 seconds

after lift-off. In fact, we can use logical reasoning to conclude that this number

I = ![]() is

the exact number of feet by which the altitude increased ; that is,

is

the exact number of feet by which the altitude increased ; that is, ![]() =

= ![]() .

.

The argument goes like this: Given any partition P of [a,b] =

[0,12] , the P-Upper sum, Uf (P), is an estimation of the

increase in rocket altitude which assumes that, during each sub-interval of the

partition P, the velocity of the rocket was constant and equal to maximum

velocity of the rocket during that sub-interval. The assumption of constant

velocity at the maximum velocity of each sub-interval means that this Upper sum

estimation will be an over-estimation of the actual increase in altitude: ![]() <

or =

Uf (P) .

<

or =

Uf (P) .

Likewise, the P-Lower sum, Lf (P), is an

estimation of the increase in rocket altitude which assumes that, during each

sub-interval of the partition P, the velocity of the rocket was constant and

equal to the minimum velocity of the rocket during that sub-interval.

The assumption of constant velocity at the minimum velocity of each

sub-interval means that this Lower sum estimation will be an under-estimation

of the actual increase in altitude: Lf (P) < or =

![]() .

.

Thus, for every partition P of [a,b] = [0,12], we have that: Lf

(P) < or = ![]() < or = Uf

(P)

. There is only one number that can fit "in-between" all the lower and

upper

sums of f, and that number is the Definite Integral I =

< or = Uf

(P)

. There is only one number that can fit "in-between" all the lower and

upper

sums of f, and that number is the Definite Integral I = ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() also

fits "in-between" all the lower and upper sums of f, it must be true then

that

also

fits "in-between" all the lower and upper sums of f, it must be true then

that ![]() =

= ![]() . The

techniques of Calculus to be discussed later will enable us to determine that,

for f(x) = the rocket velocity function specified above,

. The

techniques of Calculus to be discussed later will enable us to determine that,

for f(x) = the rocket velocity function specified above, ![]() = 412.50

. Thus, we can conclude that the exact amount of increase in rocket altitude

during the first 12 seconds after lift-off was 412.50 feet; that is,

= 412.50

. Thus, we can conclude that the exact amount of increase in rocket altitude

during the first 12 seconds after lift-off was 412.50 feet; that is,

![]() =

= ![]() = 412 ½ feet

= ( ( Altitude at x = 12 ) – ( Altitude at x = 0 ) )

= 412 ½ feet

= ( ( Altitude at x = 12 ) – ( Altitude at x = 0 ) )

In General, if y = f(x) is a function which calculates the rate of

change of another function, y = F(x), at every number x in an interval

[a,b], (that is, F(x) is a function with F '(x) = f(x) ), then the

amount ![]() of net

change in the value of F(x) from x = a to x = b is equal to the Definite

Integral of f(x) over the interval [a,b] ; that is,

of net

change in the value of F(x) from x = a to x = b is equal to the Definite

Integral of f(x) over the interval [a,b] ; that is,

![]() =

= ![]() =

F(b) – F(a) =

=

F(b) – F(a) = ![]() .

.

(This fact is one of the "Fundamental Theorems of Integral Calculus".)

Now, this integral I = ![]() is sandwiched in-between all

the lower sums and all the upper sums computed over all partitions P of interval

[a,b] . In fact, as the number n, the # of sub-intervals, increases

from partition to partition, with n approaching Infinity, and as

the

maximum sub-interval width, ||P||, approaches 0 ,

is sandwiched in-between all

the lower sums and all the upper sums computed over all partitions P of interval

[a,b] . In fact, as the number n, the # of sub-intervals, increases

from partition to partition, with n approaching Infinity, and as

the

maximum sub-interval width, ||P||, approaches 0 ,

the lower sum for each partition increases closer and closer to the

integeral I = ![]() . We summarize this fact by

writing: As

. We summarize this fact by

writing: As ![]() Infinity ,

Infinity , ![]() .

Similarly, as the maximum sub-interval width, ||P||, approaches 0 , the upper

sum for each partition decreases closer and closer to the integeral I =

.

Similarly, as the maximum sub-interval width, ||P||, approaches 0 , the upper

sum for each partition decreases closer and closer to the integeral I = ![]() . We

summarize this fact by writing: As

. We

summarize this fact by writing: As ![]() Infinity,

Infinity, ![]() .

.

Riemann Sums S*(P)

For a given function f , and a given interval [a,b] , these lower sums and upper sums of f for various partitions P of [a,b] are themselves special cases of a more general calculation to approximate the increase in rocket altitude ( or to approximate the net change in F(x) ), a calculation called a Riemann Sum S*(P).

Suppose, for a given partition P of [a,b], with n sub-intervals, we select n numbers, x*1 from sub-interval1, x*2 from sub-interval2, . . . , x*n from sub-intervaln, that is, we select one x*i from each sub-interval of the partition P. We approximate the increase in rocket altitude by assuming that the velocity during each sub-intervali is the actual velocity f(x*i) of the rocket at the selected point x*i . The resulting summation approximation is called the Riemann Sum S*(P) for f relative to the choices of xi*'s :

Riemann Sum ![]() .

.

Some common choices for the x*i's are these:

1) x*i = the left-hand endpoint of sub-interval i

= ![]() , ( i = 1, 2,

. . ., n) : x*i = x ( i – 1 )

.

, ( i = 1, 2,

. . ., n) : x*i = x ( i – 1 )

.

2) x*i = the right-hand endpoint of sub-interval

i = ![]() , ( i = 1, 2,

. . . , n )

: x*i = x i .

, ( i = 1, 2,

. . . , n )

: x*i = x i .

3) x*i = the midpoint of sub-interval i , (

i = 1, 2, . . ., n) : x*i = ![]() .

.

There are many other possible choices for the x*i's, and

each

new selection of the x*i's can produce a new Riemann Sum S*(P)

calculation. But, as the partitions P that we use become finer and finer, as

the maximum sub-interval width ||P|| approaches 0 , these Riemann Sum

S*(P) calculations also approach closer and closer to the limit I = ![]() . We

summarize this fact by writing:

. We

summarize this fact by writing:

As ![]() Infinity ,

Infinity , ![]() . That is, as

. That is, as ![]() Infinity,

Infinity, ![]() .

.

It is this fact, in fact, that explains why the notation for the definite

integral is what it is: the notation reminds us that this special number, I

= ![]() is

the limit of sums

is

the limit of sums![]() of terms, each of which is a

product of the form

of terms, each of which is a

product of the form ![]() computed over the interval

[a,b] . We can imagine that, in the limit process, the

computed over the interval

[a,b] . We can imagine that, in the limit process, the ![]() turn into the

turn into the ![]() symbol,

the f(x*i)'s turn into the function f(x), and the

symbol,

the f(x*i)'s turn into the function f(x), and the ![]() 's

turn

into dx .

's

turn

into dx .

In the rest of this handout, we will use geometry to verify that the

number I = ![]() is actually equal to 412.5,

and so for the rocket velocity function f(x) we have been analyzing, the

increase in rocket altitude in the first 12 seconds after lift-off is actually

412.5 feet.

is actually equal to 412.5,

and so for the rocket velocity function f(x) we have been analyzing, the

increase in rocket altitude in the first 12 seconds after lift-off is actually

412.5 feet.

But first, it is important to mention one important fact about the possible values of the definite integral

I = ![]() . That is, if the function

f(x) is continuous and is such that y = f(x) < 0 for every

. That is, if the function

f(x) is continuous and is such that y = f(x) < 0 for every ![]() , then the

definite integral I =

, then the

definite integral I = ![]() is also negative, that is,

is also negative, that is,

![]() <

0 also. This is because, for every partition P of [a,b], the maximum

f(x)-values Mi on the sub-intervals will themselves be negative

numbers and the upper sums, Uf (P) =

<

0 also. This is because, for every partition P of [a,b], the maximum

f(x)-values Mi on the sub-intervals will themselves be negative

numbers and the upper sums, Uf (P) = ![]() , will all be

negative totals also. These upper sums will decrease (become even more

negative) down toward the definite integral

, will all be

negative totals also. These upper sums will decrease (become even more

negative) down toward the definite integral ![]() , which must then be negative

too. It is even possible that, on one sub-interval of [a,b], y = f(x) <

0, and on another sub-interval of [a,b], y = f(x) > 0, in such a way that

I =

, which must then be negative

too. It is even possible that, on one sub-interval of [a,b], y = f(x) <

0, and on another sub-interval of [a,b], y = f(x) > 0, in such a way that

I = ![]() =

0 .

=

0 .

Geometrical Verification that ![]() =

= ![]() = 412 ½

feet

= 412 ½

feet

We have seen that ![]() =

= ![]() already, but we can

use geometry to show that

already, but we can

use geometry to show that ![]() = 412.5.

= 412.5.

OBSERVATION: When y = f(x) > or = 0 on [a,b], and when P is a

partition of interval [a,b], and when numbers ![]() 's have been chosen from the

sub-intervali's, then for each term

's have been chosen from the

sub-intervali's, then for each term ![]() , calculated when

computing the summation S*(P) , that term

, calculated when

computing the summation S*(P) , that term ![]() also calculates the area of a

rectangle on the graph of y = f(x); it is the area of the rectangle built with

base along the x-axis, situated directly on sub-intervali, and with

the height of the rectangle equal to the function value f(xi) at the

selected point xi in that ith sub-interval.

also calculates the area of a

rectangle on the graph of y = f(x); it is the area of the rectangle built with

base along the x-axis, situated directly on sub-intervali, and with

the height of the rectangle equal to the function value f(xi) at the

selected point xi in that ith sub-interval.

The Rieman Sum S*(P) is the summation of these terms, and this summation is also the summation of the areas of these rectangles, and so the summation S*(P) can be viewed as an approximation to the area ACurve of the region of the plane which lies under the curve y = f(x), above the x-axis, and between the lines x = a and x = b , two lines which are perpendicular to the x-axis at the endpoints of the given interval [a,b].

For example, we compute the Riemann Sum S*(P) using the rocket velocity

function y = f(x) defined at the start of this handout, and using the

partition P2 = { 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 } , and using a particular

selection of numbers for the x*i's, namely, x*1 =

1.5, x*2 = 4.5, x*3 = 7.5 and x*4 =

11 . The relevant function values are f(x*1) = f(1.5) = 15 ; f(x*2)

= f(4.5) = 30 ; f(x*3) = f(7.5) = 37.5 ; and f(x*4)

= f(11) = 60 . The sub-interval widths are all ![]() = 3 . Thus, the

Riemann Sum S*(P) here is:

= 3 . Thus, the

Riemann Sum S*(P) here is:

S*(P) = ![]() = (15) (3) + (30) (3) +

(37.5) (3) + (60) (3) = 427.5 . This is also the sum of the areas of

the rectangles shaded in the graph below:

= (15) (3) + (30) (3) +

(37.5) (3) + (60) (3) = 427.5 . This is also the sum of the areas of

the rectangles shaded in the graph below:

The 1st rectangle has area = f(1.5) *![]() = (15)*(3) = 45 .

= (15)*(3) = 45 .

The 2nd rectangle has area = f(4.5) *![]() = (30)*(3) = 90

.

= (30)*(3) = 90

.

The 3rd rectangle has area = f(7.5) *![]() = (37.5)*(3) =

112.5 .

= (37.5)*(3) =

112.5 .

The 4th rectangle has area = f(11) *![]() = (60)*(3) = 180.

= (60)*(3) = 180.

The total area of the shaded region is 45 + 90 + 112.5 + 180 = 427.5 = S*(P) .

S*(P) = the area of this shaded region !

Now, since all of the Riemann Sums S*(P) for this function f(x) and for all the partitions of [a,b] can be viewed as calculating the sum of areas of rectangles and as approximations of ACurve , the area under the curve and above the interval [a,b] on the x-axis, so too can all the Upper sums Uf (P) and all of the Lower sums Lf (P) be viewed as approximations to this area. But, when we compare these Lf (P) and Uf (P) approximations to the actual area under curve, ACurve , we find that, for all partitions P,

Lf (P) < or = ACurve < or = Uf (P) .

For example, the graphs below demonsrate this using

the partition P = P2 :

For example, the graphs below demonsrate this using

the partition P = P2 :

For the computation of Lf (P) , in the summation

S*(P), we will use the following as the selected numbers![]() : For the ith

sub-interval,

: For the ith

sub-interval,![]() = that number x in the

sub-interval such that f(

= that number x in the

sub-interval such that f(![]() ) = m i .

In this case then,

) = m i .

In this case then,

Lf (P) = S*(P) =

= (0)(3) + (20)(3) + (30)(3) + (40)(3)

= 0 + 60 + 90 + 120 = 270

= the area of the shaded region.

For the computation of Uf (P) , in

the summation S*(P), we will use the following as the selected numbers

For the computation of Uf (P) , in

the summation S*(P), we will use the following as the selected numbers ![]() : For the ith

sub-interval,

: For the ith

sub-interval,![]() = that number x in the

sub-interval such that f(

= that number x in the

sub-interval such that f(![]() ) = M i .

In this case then,

) = M i .

In this case then,

Uf (P) = S*(P) =

= (30)(3) + (40)(3) + (45)(3) + (70)(3)

= 90 + 120 + 135 + 210 = 555

= the area of the shaded region.

If you look closely at the two graphs above, you will

see that the region with the area equal to Lf (P) lies

completely within the region under the curve. If you think about it, you will

see that this is going to be true for every partition P of [a,b] = [0,12] .

So, for every partition P of [a,b], Lf (P) < or = ACurve

= the area under the curve.

If you look closely at the two graphs above, you will

see that the region with the area equal to Lf (P) lies

completely within the region under the curve. If you think about it, you will

see that this is going to be true for every partition P of [a,b] = [0,12] .

So, for every partition P of [a,b], Lf (P) < or = ACurve

= the area under the curve.

You will also see that the region under the curve lies completely within the region with the area equal to U f (P), and this will be true for all partitions P of [a,b] = [0,12] . So, for every partition P of [a,b], ACurve < or = Uf (P) .

Since the area under the curve ACurve is "in-between" all

of the Lower sums and all of the Upper sums of all partitions P of [a,b] =

[0,12] , it must also be true that ACurve is equal to that special

number I = ![]() .

.

The region under this particular curve is made up of a triangle and four

(4) trapezoids, formed by drawing vertical lines perpendicular to the x-axis

at x = 4, 5, 7, and 8. It is a simple matter to calculate the areas of these

trapezoids, and the sum their areas is equal to 412.5 square units. This

verifies the earlier assertion that ![]() = 412.5 and verifies that

the increase in rocket altitude during the first 12 seconds after lift-off is

exactly 412.5 feet.

= 412.5 and verifies that

the increase in rocket altitude during the first 12 seconds after lift-off is

exactly 412.5 feet.