Home

Integration by Parts

Integration by PartsExamples

Integration by Parts with a definite integral

Going in Circles

Tricks of the Trade

Integrals of Trig Functions

Antiderivatives of Basic Trigonometric FunctionsProduct of Sines and Cosines (mixed even and odd powers or only odd powers)

Product of Sines and Cosines (only even powers)

Product of Secants and Tangents

Other Cases

Trig Substitutions

How Trig Substitution WorksSummary of trig substitution options

Examples

Completing the Square

Partial Fractions

Introduction to Partial FractionsLinear Factors

Irreducible Quadratic Factors

Improper Rational Functions and Long Division

Summary

Strategies of Integration

SubstitutionIntegration by Parts

Trig Integrals

Trig Substitutions

Partial Fractions

Improper Integrals

Type 1 - Improper Integrals with Infinite Intervals of IntegrationType 2 - Improper Integrals with Discontinuous Integrands

Comparison Tests for Convergence

Modeling with Differential Equations

IntroductionSeparable Equations

A Second Order Problem

Euler's Method and Direction Fields

Euler's Method (follow your nose)Direction Fields

Euler's method revisited

Separable Equations

The Simplest Differential EquationsSeparable differential equations

Mixing and Dilution

Models of Growth

Exponential Growth and DecayThe Zombie Apocalypse (Logistic Growth)

Linear Equations

Linear ODEs: Working an ExampleThe Solution in General

Saving for Retirement

Parametrized Curves

Three kinds of functions, three kinds of curvesThe Cycloid

Visualizing Parametrized Curves

Tracing Circles and Ellipses

Lissajous Figures

Calculus with Parametrized Curves

Video: Slope and AreaVideo: Arclength and Surface Area

Summary and Simplifications

Higher Derivatives

Polar Coordinates

Definitions of Polar CoordinatesGraphing polar functions

Video: Computing Slopes of Tangent Lines

Areas and Lengths of Polar Curves

Area Inside a Polar CurveArea Between Polar Curves

Arc Length of Polar Curves

Conic sections

Slicing a ConeEllipses

Hyperbolas

Parabolas and Directrices

Shifting the Center by Completing the Square

Conic Sections in Polar Coordinates

Foci and DirectricesVisualizing Eccentricity

Astronomy and Equations in Polar Coordinates

Infinite Sequences

Approximate Versus Exact AnswersExamples of Infinite Sequences

Limit Laws for Sequences

Theorems for and Examples of Computing Limits of Sequences

Monotonic Covergence

Infinite Series

IntroductionGeometric Series

Limit Laws for Series

Test for Divergence and Other Theorems

Telescoping Sums

Integral Test

Preview of Coming AttractionsThe Integral Test

Estimates for the Value of the Series

Comparison Tests

The Basic Comparison TestThe Limit Comparison Test

Convergence of Series with Negative Terms

Introduction, Alternating Series,and the AS TestAbsolute Convergence

Rearrangements

The Ratio and Root Tests

The Ratio TestThe Root Test

Examples

Strategies for testing Series

Strategy to Test Series and a Review of TestsExamples, Part 1

Examples, Part 2

Power Series

Radius and Interval of ConvergenceFinding the Interval of Convergence

Power Series Centered at $x=a$

Representing Functions as Power Series

Functions as Power SeriesDerivatives and Integrals of Power Series

Applications and Examples

Taylor and Maclaurin Series

The Formula for Taylor SeriesTaylor Series for Common Functions

Adding, Multiplying, and Dividing Power Series

Miscellaneous Useful Facts

Applications of Taylor Polynomials

Taylor PolynomialsWhen Functions Are Equal to Their Taylor Series

When a Function Does Not Equal Its Taylor Series

Other Uses of Taylor Polynomials

Functions of 2 and 3 variables

Functions of several variablesLimits and continuity

Partial Derivatives

One variable at a time (yet again)Definitions and Examples

An Example from DNA

Geometry of partial derivatives

Higher Derivatives

Differentials and Taylor Expansions

Differentiability and the Chain Rule

DifferentiabilityThe First Case of the Chain Rule

Chain Rule, General Case

Video: Worked problems

Multiple Integrals

General Setup and Review of 1D IntegralsWhat is a Double Integral?

Volumes as Double Integrals

Iterated Integrals over Rectangles

How To Compute Iterated IntegralsExamples of Iterated Integrals

Fubini's Theorem

Summary and an Important Example

Double Integrals over General Regions

Type I and Type II regionsExamples 1-4

Examples 5-7

Swapping the Order of Integration

Area and Volume Revisited

Double integrals in polar coordinates

dA = r dr (d theta)Examples

Multiple integrals in physics

Double integrals in physicsTriple integrals in physics

Integrals in Probability and Statistics

Single integrals in probabilityDouble integrals in probability

Change of Variables

Review: Change of variables in 1 dimensionMappings in 2 dimensions

Jacobians

Examples

Bonus: Cylindrical and spherical coordinates

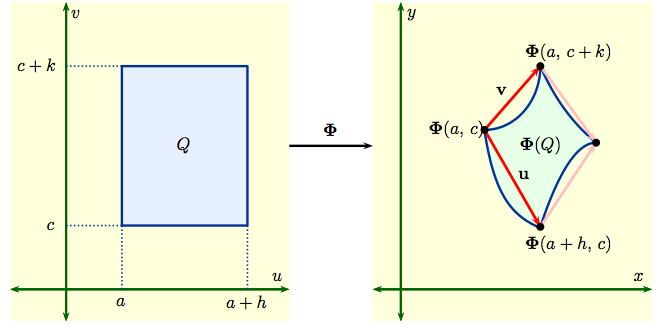

The distortion factor between size in $uv$-space and size in $xy$ space is called the Jacobian. The following video explains what the Jacobian is, how it accounts for distortion, and how it appears in the change-of-variable formula.

| Definition: The Jacobian of the transformation $${\bf \Phi}: (u,\,v) \ \longrightarrow \ (x(u,\, v), \, y(u, \,v))$$ is the $2\, \times\, 2$ determinant $$\frac{\partial (x,\,y)}{\partial (u, \,v)} \ = \ \left|\,\begin{matrix}\displaystyle { \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}} & \displaystyle { \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} } \cr \\ \displaystyle { \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} }& \displaystyle { \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}} \end{matrix}\,\right|\,\ = \ \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} - \frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}.$$ Note that the bars around the $2 \times 2$ matrix mean ''determinant'', not absolute value. The Jacobian $\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$ may be positive or negative. |

| Change-of-variable formula: If a 1-1 mapping $\Phi$ sends a region $D^*$ in $uv$-space to a region $D$ in $xy$-space, then $$\iint_D f(x,y) dx\,dy \ = \ \iint_{D^*} f(\Phi(u,v)) \left | \frac{\partial(x,y)} {\partial(u,v)} \right | du\, dv. $$ Note that this involves the absolute value of the Jacobian. Even when the Jacobian is negative, the distortion in volume is positive. |

| Example 1: Compute the Jacobian of the polar coordinates transformation $$x \ = \ r \cos \theta,\, \qquad y = r \sin \theta\,.$$ Solution: Since \begin{eqnarray*} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial r} = \cos(\theta), \quad & \frac{\partial y}{\partial r} = \sin(\theta), \\ & \frac{\partial x}{\partial \theta} = -r \sin(\theta), \quad & \frac{\partial y}{\partial \theta} = r \cos(\theta), \end{eqnarray*} | our Jacobian is $$ \left|\begin{matrix} \displaystyle { \frac{\partial x}{\partial r} }& \displaystyle{\frac{\partial x}{\partial \theta} }\cr \\ \displaystyle { \frac{\partial y}{\partial r} }& \displaystyle { \frac{\partial y}{\partial \theta}} \end{matrix}\right|\ = \ \left|\begin{matrix} \cos \theta & -r\sin \theta \cr \\ \sin \theta & r \cos \theta \end{matrix}\right|\ = \ r\,.$$ This explains why there's an $r$ factor in polar integrals! The area element $dA=dx\,dy$ is not equal to $dr\,d\theta$. Instead, $dA$ is equal to $r\, dr\,d\theta$. |

Let's see why the Jacobian is the distortion factor in general for a mapping $${\bf \Phi} : (u,\, v) \ \to \ (x(u,\,v),\, y(u,\,v)) \ = \ x(u,\,v)\, {\bf i} +y(u,\,v)\, {\bf j}\,, $$ making good use of all the vector calculus we've developed so far. Let $Q = [a,\,a+h]\times [c,\,c+k]$ be a rectangle in the $uv$-plane and ${\bf \Phi}(Q)$ its image in the $xy$-plane as shown in

Then $${\bf u} \ = \ {\bf \Phi}(a+h,\,c) - {\bf \Phi}(a,\,c)\,, \qquad {\bf v} \ = \ {\bf \Phi}(a,\,c+k) - {\bf \Phi}(a,\,c)\,.$$ The area of the parallelogram spanned by ${\bf u} = u_1 {\bf i} + u_2 {\bf j}$ and ${\bf v} = v_1 {\bf i} + v_2 {\bf j}$ is the determinant $\left | \begin{matrix} u_1 & v_1 \cr u_2 & v_2 \end{matrix}\right |$.

By the definition of partial derivatives, $$\frac{{\bf \Phi}(a+h,\,c) - {\bf \Phi}(a,\,c)}{h} \ \approx \ \frac{\partial {\bf \Phi}}{\partial u}\Big|_{(a,c)}\ = \ \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\Big|_{(a,c)}\, {\bf i} + \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\Big|_{(a,c)}\, {\bf j} \,,$$ $$\frac{{\bf \Phi}(a,\,c+k) - {\bf \Phi}(a,\,c)}{k} \ \approx \ \frac{\partial {\bf \Phi}}{\partial v}\Big|_{(a,c)}\ = \ \frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\Big|_{(a,c)}\, {\bf i} + \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\Big|_{(a,c)}\, {\bf j}\,.$$ We then compute $$\hbox{area}(\Phi(Q)) \approx \left | \begin{matrix} u_1 & v_1 \cr u_2 & v_2 \end{matrix}\right | \ \approx \ \left | \begin{matrix} h \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & k \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} \cr h \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & k \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} \end{matrix} \right | \ = \ hk \left | \begin{matrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} \cr \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{matrix} \right |. $$

| Since $\hbox{area}(Q) \, =\, hk$, this means that the area of our region in the $xy$ plane is given by the absolute value of the Jacobian times the area in the $uv$ plane. Our shorthand for this is $$dA \ = \ dx\, dy \ = \ \left | \frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)} \right | du \, dv.$$ |

So why didn't we see an absolute value in the change-of-variables formula in one dimension? This had to do with the way we write the limits of integration.

|

Example 2: Compute $\int_0^{10} e^{-x/5} dx$. Solution: We did this before using $x=g(u)=5u$. Instead, let's take $x=-5u$, so $g'(u)=-5$ is negative. Now $e^{-x/5}=e^u$ and $dx= -5 du$. The map $g$ sends the interval from 0 to -2 in $u$-space to the interval from 0 to 10 in $x$-space, and our change-of-variable formula says $$\int_0^{10} e^{-x/5} dx \ = \ \int_0^{-2} -5 e^{u} du.$$ Of course, we usually integrate from $-2$ to $0$, not from $0$ to $-2$. |

Flipping the limits of integration changes the sign of the answer, so

$$\int_0^{10} e^{-x/5} dx \ = \ \int_{-2}^{0} +5 e^{u} du = 5(1-e^{-2}).$$

If we had written our 1-dimensional integrals in terms of regions instead in terms of starting points and end points, we would have had a factor of $+5$, rather than $-5$, all along. The mapping $x=-5u$ sends the region $D^*=[-2,0]$ to the region $D=[0,10]$, and $$\int_D e^{-x/5} dx \ = \ \int_{D^*} e^u \left | \frac{dx}{du} \right| du.$$ |